New interactive sculpture in Luddy Hall is ‘not human, but alive’

| Emily Isaacman | Indiana Daily Student

"Amatria" is a luminous and interactive sculptural landscape located in the atrium of Luddy Hall. The sculpture is comprised of 3D-printed formations and mesh-like canopies filled with pulsing mechanisms. Read original article.

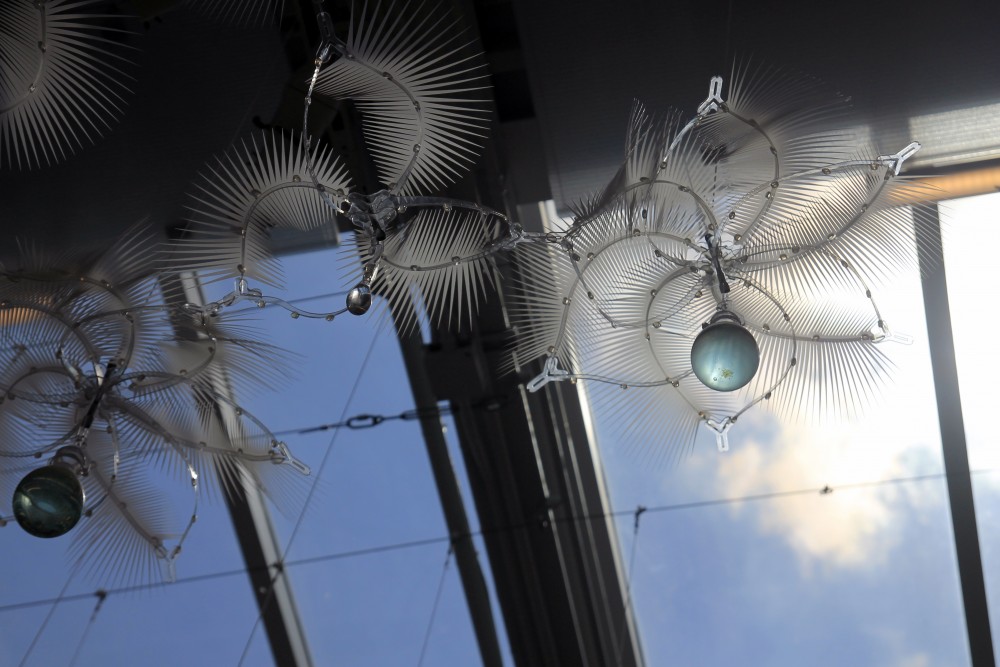

Bristling white fronds, tubes of geometric wiring and fluid-filled glass bulbs hang within a creature-like installation swooping above the central staircase in Luddy Hall.

Brightly lit by small LED spotlights, the structure whispers, vibrates and flashes light in response to movements in its surroundings.

The sculpture's name is Amatria.

“It provides an engaging, interactive, computerized environment that feels not human, but alive,” Ph.D. student Andreas Bueckle said.

Portions of the interactive art installation can be seen from any vantage point on the fourth floor of Luddy Hall, the state-of-the-art facility that opened in January 2018 and houses the departments of computer science, information and library science and intelligent systems engineering.

Canadian artist and architect Phillip Beesley calls his work sentient architecture, referring to the combination of art, architecture and intelligent system technology that composes the seemingly living landscape.

Engineering and Information Science professor Katy Börner met Beesley at a conference two and a half years ago, and she helped enlist his work as Luddy Hall was being constructed.

He visited campus several times over the past few years to plan and assemble 3-D-printed materials, artificial intelligence and sensors for the installation.

Amatria is an intelligent system that gathers, processes and reacts to information from its surroundings, reflecting the core of the Intelligent Systems Engineering program with which it shares a home, Bueckle said.

In addition to enhancing the building's public space, Bueckle said Amatria will serve as a learning tool for students, researchers and public visitors.

Beesley invited students, faculty and community members to volunteer in building and installing pieces of the massive structure.

Junior Clara Fridman said it was difficult for her to imagine how the tiny sticks, whiskers and branches she worked to assemble would fit into the final product.

“Those are the parts you don’t think about when you see the finished picture,” Fridman said.

Although its clear thicket of interlocking wires and bulbs appear dense on first glance, closer inspection reveals an intricate network of tiny parts.

The web even wraps through green exit signs hanging low from the ceiling.

The sculpture’s light, motion and sound sensors and motor actuators allow students to practice creating codes that wirelessly communicate with its data streams.

A new course being offered next fall, E484: Scientific Visualization, will use the sculpture to teach data visualization, which is the presentation of data through pictures and graphs.

Bueckle, whose research focuses on data visualization literacy, said bioengineers, neuroengineers and researchers in his field have expressed interest in using the artificial organism for research.

“People have a natural curiosity towards her,” Bueckle said.

He worked closely with Beesley to develop an app called Tavola to work in tandem with the sculpture. While the app is not yet available for public use, Bueckle said it will eventually help teach visitors why and how Amatria acts the way it does.

The app has two features, which Bueckle refers to as stories. The first story displays a zoomable, rotatable 3-D model of Amatria to help visitors locate and understand its technical aspects, such as sensors, speakers and microprocessors.

The second story depicts how two of Amatria’s 18 infrared sensors respond to movement in its surroundings in real time.

These sensors, distributed in six pods of small, low-hanging black boxes around the sculpture, measure distances to foreign objects and generate reactive lights, sounds and vibrations nearby.

Amatria’s constant shifts and noises cause many passers-by to slow their tracks, heads craned upward and mouths gaped open, as they emerge from the stairwell beneath it.

Some stop to take pictures or videos with their iPhones. Others take cautious steps beneath the canopy, observing how it reacts to their movements. One man waved his hand above his head and whistled as if ordering the wires to come alive.

Martin Shedd, a visiting professor of classical studies, ventured to Luddy Hall specifically to view the sculpture after he read about it in a recent report.

“It’s intriguing, that’s for sure,” Shedd said.

After spending a few minutes studying Amatria from multiple angles, Shedd said its various components made it hard for him to form a single impression of its aesthetic.

“It’s kind of like the White Witch of Narnia majored in electrical engineering,” Shedd said.

Because of its public charm, Börner said she expects Amatria to be as iconic to Luddy Hall as the Sample Gates are to IU.

“Amatria is a physical manifestation of ISE’s mission to create the next generation of ‘renaissance engineers,’ fluent in art, science and technology,” Börner said in an April 24 email.

Luddy Hall offers public tours of Amatria every few weeks, including this Wednesday.

While the artwork was officially revealed April 11, during the weeklong LuddyFest leading up to the building’s dedication ceremony April 13, Fridman said it will grow and evolve as people develop programming for it.

“The best is yet to come,” Fridman said.

Additional Photos